Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

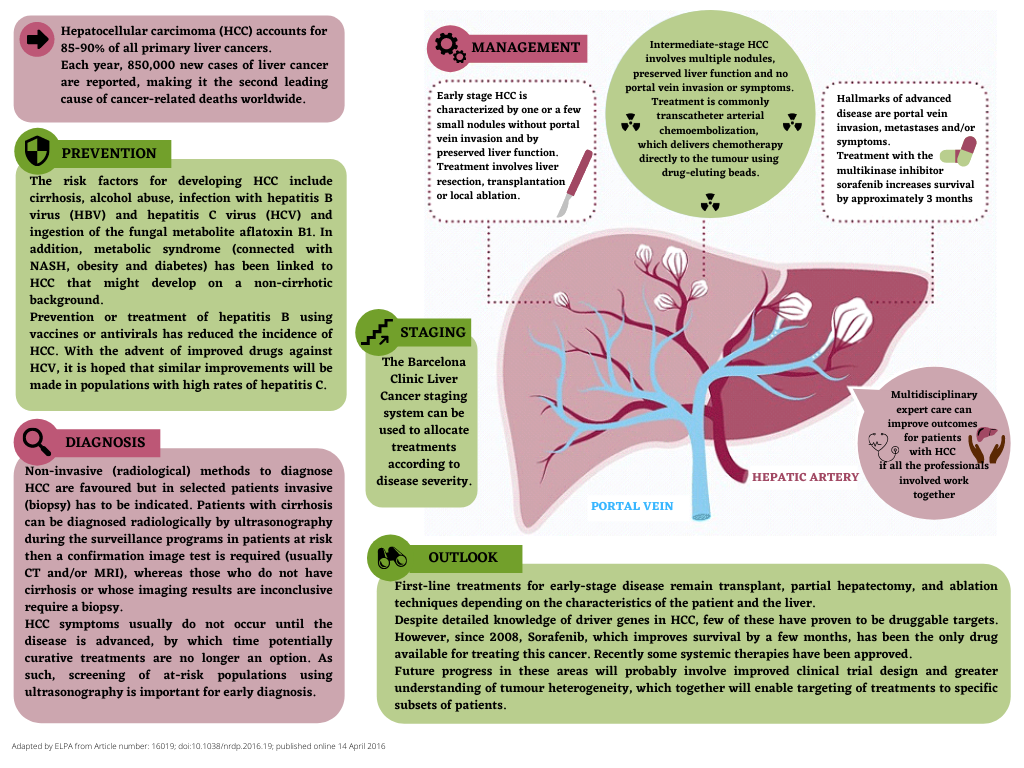

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver cancer, and it usually occurs in people with liver cirrhosis, but it can also occur in non-cirrhotic liver tissue, especially in patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and in patients with MASLD. The other types of primary liver cancer – intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and hepatoblastoma – are much less common. HCC is considered to be one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths worldwide.

Both the incidence and mortality of HCC are increasing worldwide, making it a growing public health issue. HCC diagnosed at an early stage has a far better prognosis than HCC diagnosed at a late stage, mainly because early-stage HCC can be treated with potentially curative therapies.

PREVENTION

Primary prevention focuses on risk factors for HCC and their preventative measures and treatments. Nowadays, the actions and treatment to prevent HCC consist of universal HBV vaccination and wide implementation of anti-HBV therapy, when indicated, and direct-acting antiviral agents against HCV. They are crucial and likely to change the worldwide etiologic landscape of HCC. However, to prevent the complications of chronic HBV infection, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends including hepatitis B vaccination in routine immunization services in all countries (universal vaccination starting with the newborn vaccination and particularly vaccination programs for adult people at risk).

Another essential strategy to prevent HCC related to chronic viral hepatitis is testing blood products for HBV and HCV and adopting actions to avoid transmission of HBV and HCV in healthcare settings.

At present, Chronic Alcoholic Liver Disease (ALD) has become one of the leading risk factors for HCC. Since these patients are frequently missed by surveillance programs, when they are diagnosed with HCC, the stage of their tumour is usually advanced. Therefore, it is imperative to carry out early diagnosis of ALD and management of cirrhosis-related complications. Moreover, the increasing incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (MASLD/MASH), together with metabolic syndrome and obesity, amplifies the risk of liver cancer. The broad implementation of HCC awareness and surveillance in high-risk patients is essential to reduce the high mortality from HCC.

EARLY DETECTION IN PEOPLE WITH RISK FACTORS

The risk of developing HCC is higher in people with cirrhosis due to HBV, HCV, alcohol, or MASLD/MASH. People with liver cirrhosis need abdominal ultrasound with or without analysis with alpha-fetoprotein every 6 months. The risk of HCC in former HCV patients is reduced but does not go away, particularly in patients with advanced fibrosis. Moreover, the risk of HCC is higher if there is obesity and/or diabetes

SURVEILLANCE

The decision to register a patient for a surveillance programme is determined by the risk of having HCC. Different factors such as age, co-morbidities, liver function, etc., should be taken into account. Surveillance is recommended for: patients with cirrhosis (irrespective of the etiology). Patients with hepatitis B or MASLD/MASH but no cirrhosis can develop HCC, although the annual incidence of HCC in these groups is lower than in patients diagnosed with cirrhosis. The preferred test for surveillance is ultrasonography every 6 months. Although specific data in patients with MASLD/MASH are lacking, some authors recommend novel blood tests and imaging-based surveillance strategies. HCC surveillance is underused in clinical practice, highlighting the need for interventions to identify at-risk individuals better and promote HCC surveillance completion.

DIAGNOSIS AND STAGING

Most people don’t exhibit symptoms in the early stages of HCC. However, when signs and symptoms do appear, they might be related to cancer or chronic liver disease. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is usually diagnosed through screening programs using ultrasounds every 6 months in people with cirrhosis. Once a lesion has been identified by ultrasonography, the diagnosis of HCC must be confirmed with the presence of characteristic features of an HCC using dynamic imaging tests such as CT or/and MRI with contrast that should confirm the diagnosis in a patient deemed to be at risk of the disease.

THE IMPORTANCE OF A MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM DURING ALL THE PROCESS

Patients diagnosed with HCC should be managed by a multidisciplinary team involving hepatologists, surgeons, radiologists, interventional radiologists, pathologists, and oncologists. Multidisciplinary experts sharing clinical information and decisions related to management can improve outcomes for patients with HCC.

PROGNOSTIC MODELS AND HCC STRATIFICATION

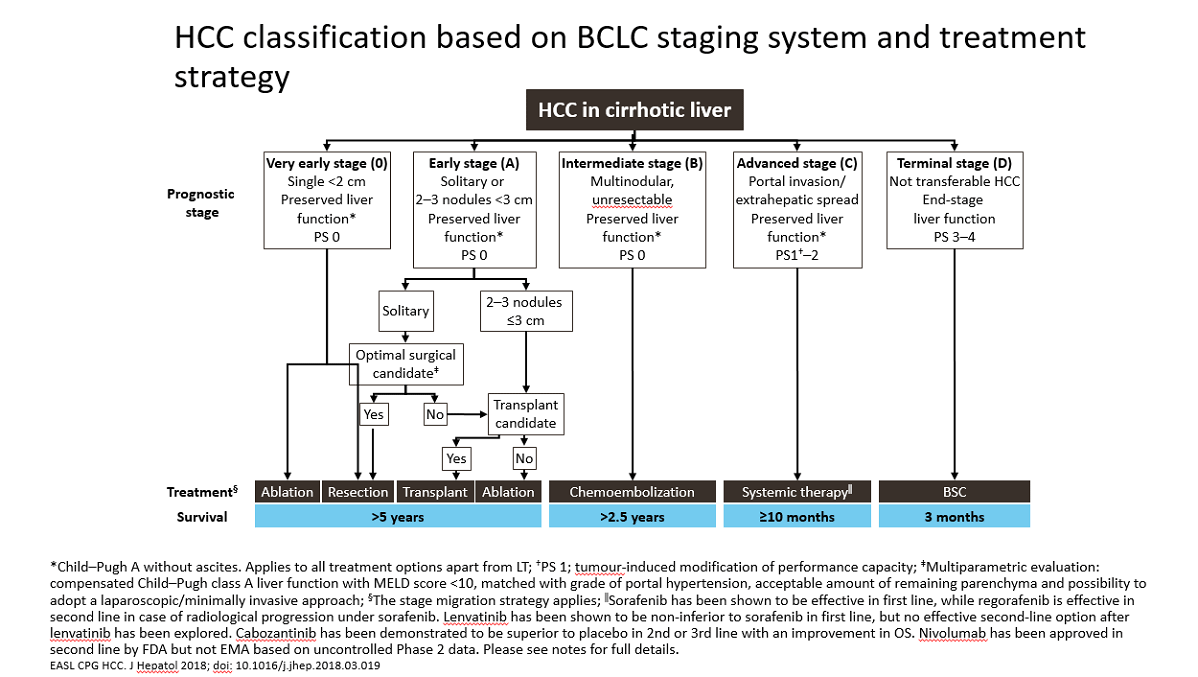

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) is the most used prognostic model for HCC. This classification categorizes the prognosis of HCC in 5 groups and guides the management of hepatocellular carcinoma, considering that, in general, HCC will need a sequential treatment. Barcelona-Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging gives a risk assessment classification and treatment schedule. Five stages are considered:

◉ Stage 0, Stage A: Patients with early HCC suitable for curative therapies: resection, liver transplantation, or percutaneous treatments (such as RFA).

◉ Stage B: Patients at the intermediate HCC stage may benefit from TACE (Transarterial chemoembolization).

◉ Stage C: Patients at the advanced HCC stage may receive, in selected cases, systemic agents or drugs in the setting of RCT.

◉ Stage D: Those patients with the end-stage disease will receive symptomatic treatment and supportive care.

CURRENT TREATMENT MODALITIES

Treatments of HCC may differ depending on the HCC stage the patient is diagnosed with. In early stages 0 or A, they include:

◉ Resection: removing the cancer and a part of healthy tissue that surrounds it.

◉ Liver transplant surgery: remove the entire liver and replace it with a liver from a deceased or living donor.

◉ Ablation: destroying cancer cells with heat or cold.

If the HCC is classified as an intermediate stage, the locoregional therapy may consist in delivering chemotherapy or radiation directly to cancer cells (TACE, Transarterial chemoembolization, or similar).

In more advanced HCC stages, treatment will be systemic and using targeted drug therapy. Targeted drugs, such as sorafenib, regorafenib, cabozantinib, nivolumab, etc., may help slow the progression of the disease in people with advanced liver cancer. In addition, psychological help in dealing with the burden of end-stage HCC should not be neglected or underestimated.

Due to the HCC characteristics, a patient has two diseases, cirrhosis and cancer, and the treatment is usually sequential and will be escalating through the stages. Patients should be managed by a multidisciplinary team to improve care and outcome.

HCC FROM PATIENTS’ AND FAMILIES’ PERSPECTIVE

Liver cancer might be associated with drug or alcohol abuse, which creates a stigma, although that is no longer the case for a large percentage of people who develop HCC. Patients’ and families’ experiences with HCC are connected to 4 major themes:

1: Illness perceptions. The perceptions of HCC covered a broad spectrum, highlighted by:

◉ Lack of information to prepare them for “the journey ahead,”

◉ Feelings of isolation,

◉ Unrealistic hopes,

◉ Feelings of lack of control.

2: Treatment confusion. Patients may experience:

◉ Uncertainty about treatments over time,

◉ Struggle with symptoms management,

◉ Doubts or regrets for receiving or not receiving treatment.

3: Quality of life. Symptoms affect everyday life, and many patients believe that the side effects compromise their quality of life.

4: Coping strategies. Patients and families experience a range of reactions to their diagnosis and develop their ways of coping.

THE ROLE OF LIVER PATIENTS’ ASSOCIATIONS

The role of Liver Patients’ Associations in HCC is crucial, and it is based on updated, and scientific information mainly focused on prevention since there is no one better than another patient to inform his peers. Patients’ associations are vital in this field since they inform in a simpler way so that patients understand better. The message must be clear, saying that we cannot play with health and cannot rely on news that can be found on the Internet or heard from a neighbour.

It is expected that patients are actively seeking medical knowledge in social media and are exposed to health-related content through these platforms. Based on ELPA’s experience, we are aware of the importance of social media to expand medical information.

Social media present an opportunity for patient education. The intersection of social media and health is unique, given its potential influence on public health. Considering patients’

perspective, social media may provide adequate context to disseminate updated information. Health education on social media could influence public health by improving health literacy, dispelling misconceptions and disinformation from inaccurate sources.

References

Abdel-Rahman O, et al. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for the development of and mortality from hepatocellular carcinoma: An updated systematic review of 81

epidemiological studies. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine. 2017;10:245–254.

Bañales JM, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: the next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:557–588.

Barrera-Saldaña HA, Fernández-Garza LE, Barrera-Barrera SA. Liquid biopsy in chronic liver disease. Ann. Hepatol. 2020;20:100197.

Cartlidge CR, et al. The utility of biomarkers in hepatocellular carcinoma: review of urine-based 1H-NMR studies – what the clinician needs to know. Int J Gen Med.

2017;10:431–442.

Chiang JK, Chih-Wen L, Kao YH. Effect of ultrasonography surveillance in patients with liver cancer: a population-based longitudinal study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015936.

Ebrahim AE, et al. Role of Fibroscan for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in hepatitis C cirrhotic patients. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med. 2020;51:134.

EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma

European Association for the Study of the Liver. Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2018;69:182–236.

Global Burden of Disease Liver Cancer Collaboration. The Burden of Primary Liver Cancer and Underlying Etiologies From 1990 to 2015 at the Global, Regional, and

National Level: Results From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1683–1691.

Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2, 16019 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.19

Hofmarcher T, Lindgren P. The cost of cancer of the digestive system in Europe. IHE report. 2020;6. IHE: The Swedish Institute for Health Economics, Lund, Sweden.

Li L, et al. The association of liver function and quality of life of patients with liver cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:66.

Lin L, Yan L, Liu Y, Qu C, Ni J, Li H. The Burden and Trends of Primary Liver Cancer Caused by Specific Etiologies from 1990 to 2017 at the Global, Regional, National,

Age, and Sex Level Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Liver Cancer. 2020;9:563–582.

Llovet JM, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021;7(6).

Mazzucco W, et al. Does access to care play a role in liver cancer survival? The ten-year (2006–2015) experience from a population-based cancer registry in Southern

Italy. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:307.

Naugler WE, et al. Building the multidisciplinary team for management of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:827–835.

O’Rourke JM, et al. Carcinogenesis on the background of liver fibrosis: Implications for the management of hepatocellular cancer. World J Gastroenterol.

2018;24:4436–4447.

Pimpin L, et al. EASL HEPAHEALTH Steering Committee. Burden of liver disease in Europe: Epidemiology and analysis of risk factors to identify prevention policies. J

Hepatol. 2018;69:718–735.

Siddique O, et al. The importance of a multidisciplinary approach to hepatocellular carcinoma. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:95–100.

Sinn DH, et al. Multidisciplinary approach is associated with improved survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0210730.

Smith 2014. Europeans Are Getting Fatter, Just Like Americans. Available from:

https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2014/05/09/311116522/europeans-are-getting-fatter-just-like-americans

Vintura, 2021. Every day counts – The impact of COVID-19 on patient access to cancer care in Europe. Available from:

https://digestivecancers.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/EFPIA_report_Every-day-counts-COVID19-Addendum_digital-V10.pdf

Vogel A, et al. ESMO Guidelines Committee. Hepatocellular carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol.

2019;30:871–873.

Vogel, Saborowsky (2021) Hepatology Snapshot: Medical Therapy of HCC. Journal of Hepatology.

WHO 2017 https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/348222/Fact-sheet-SDG-viral-hepatitis-FINAL-en.pdf

Youssef, Ehab, Richard L. Baron, and Khaled M. Elsayes. 2015. “Diagnostic Approach of Focal and Diffuse Hepatic Diseases.” In Cross-Sectional Imaging of the

Abdomen and Pelvis: A Practical Algorithmic Approach, edited by Khaled M Elsayes, 11–76.